News

Fossils reveal huge 500-million-year-old marine worms

Advertisement

The origin in the Cambrian Explosion

Fossils found during the “Cambrian Explosion” are especially interesting when it comes to the origin of life on Earth. The Cambrian Explosion refers to a period of geological time about 541 million years ago during which there was rapid diversification and the emergence of a wide variety of complex life forms.

During this period, multicellular organisms began to become more prominent and diverse, marking an important turning point in the history of life on Earth. It was during the Cambrian Explosion that many of the major animal phyla we recognize today first appeared in the fossil record.

The 500-million-year-old marine worms mentioned earlier may be linked to this explosion of diversity. They give us unique insights into the types of life that emerged and thrived in this ancient marine environment, contributing to our understanding of the evolution of life on Earth.

Unraveling a digestive system millions of years old

Examining and understanding a digestive system that is millions of years old is a challenging but extremely exciting task for paleontologists and scientists. Well-preserved fossils can offer valuable clues about the anatomy and function of the digestive systems of ancient organisms.

When studying fossils of ancient creatures, scientists can use a variety of techniques, including morphological analysis, electron microscopy, and even chemical analysis, to reconstruct how these digestive systems were structured and how they functioned.

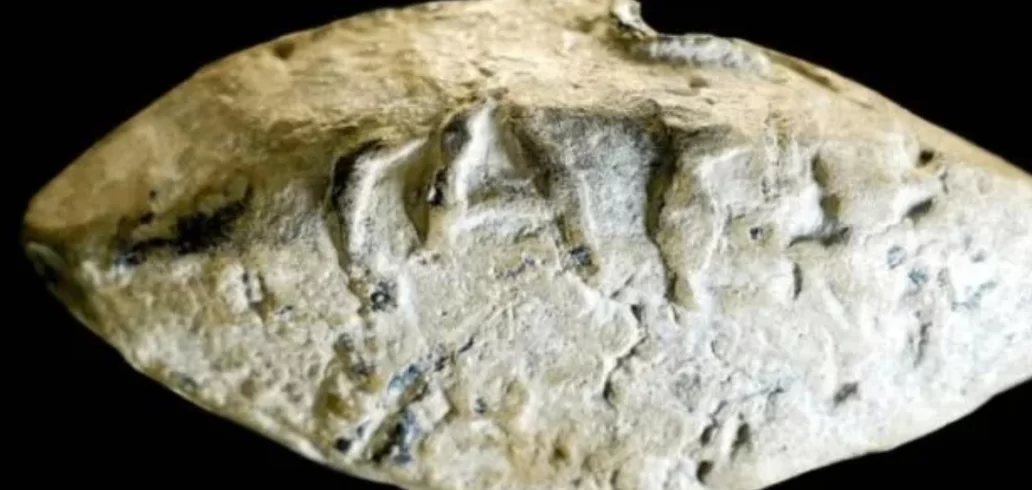

For example, marks on fossils can indicate the presence of structures such as jaws, teeth, or other organs related to feeding. Additionally, the presence of certain minerals or chemical compounds around the fossil can provide clues about the organism's diet and eating habits.

Sometimes, scientists also use comparisons with related living organisms to help reconstruct the digestive systems of extinct species. This may involve studying close modern relatives, such as mollusks, worms, or other invertebrates, to infer how the digestive systems of their extinct ancestors may have worked.

Ultimately, unraveling a digestive system millions of years old requires a combination of scientific skills, advanced technologies and a lot of dedication, but the insights we can gain into the evolutionary history of life on Earth are invaluable.

The evolution of arrowworms

Arrowworms are a fascinating group of animals that belong to the phylum Nemertea, also known as “ribbon worms” or “proboscidean worms.” They are characterized by their long, thin, often ribbon-shaped bodies and an extendable proboscis that they use to capture prey.

The evolution of arrowworms dates back hundreds of millions of years, with fossil records dating from the Cambrian to the present. Over geological time, these organisms have undergone adaptations and morphological changes to adapt to the diverse aquatic environments in which they live.

Although arrowworms are relatively simple in terms of body structure, they have evolved a number of behavioral and anatomical strategies to survive and reproduce successfully. For example, their proboscis is a remarkable adaptation that allows them to capture prey efficiently, extending rapidly to grab and wrap around their prey.

The evolution of arrowworms continues to be an active research topic for evolutionary biologists and paleontologists as they seek to better understand how these organisms have adapted and diversified over time to occupy a variety of ecological niches in aquatic ecosystems around the world.

Trending Topics

Galloway Hoard: Thousand-year-old Viking cross discovered in stunning state of preservation

Keep Reading

Cognizant offers up to S$2,150 per month and real benefits

Learn how the salary of up to US$$2,150/month works at Cognizant and understand why so many people are considering this company.

Keep Reading